09.11.2022 - belated paper on my time as an asian person at ucsb

ORIGINAL TITLE: Modeling Invisibility: Exploring Institutionalized Anti-Asian Sentiment at UCSB

author's note: upon revisiting this paper months after having written it, i must emphasize that this work is not my best. the structure and grammar is clear, but i cannot say i really even believe that what i'm writing about matters in the larger scale of things. it's not bad, it's just...trite. as with all my works, make of it what you will.

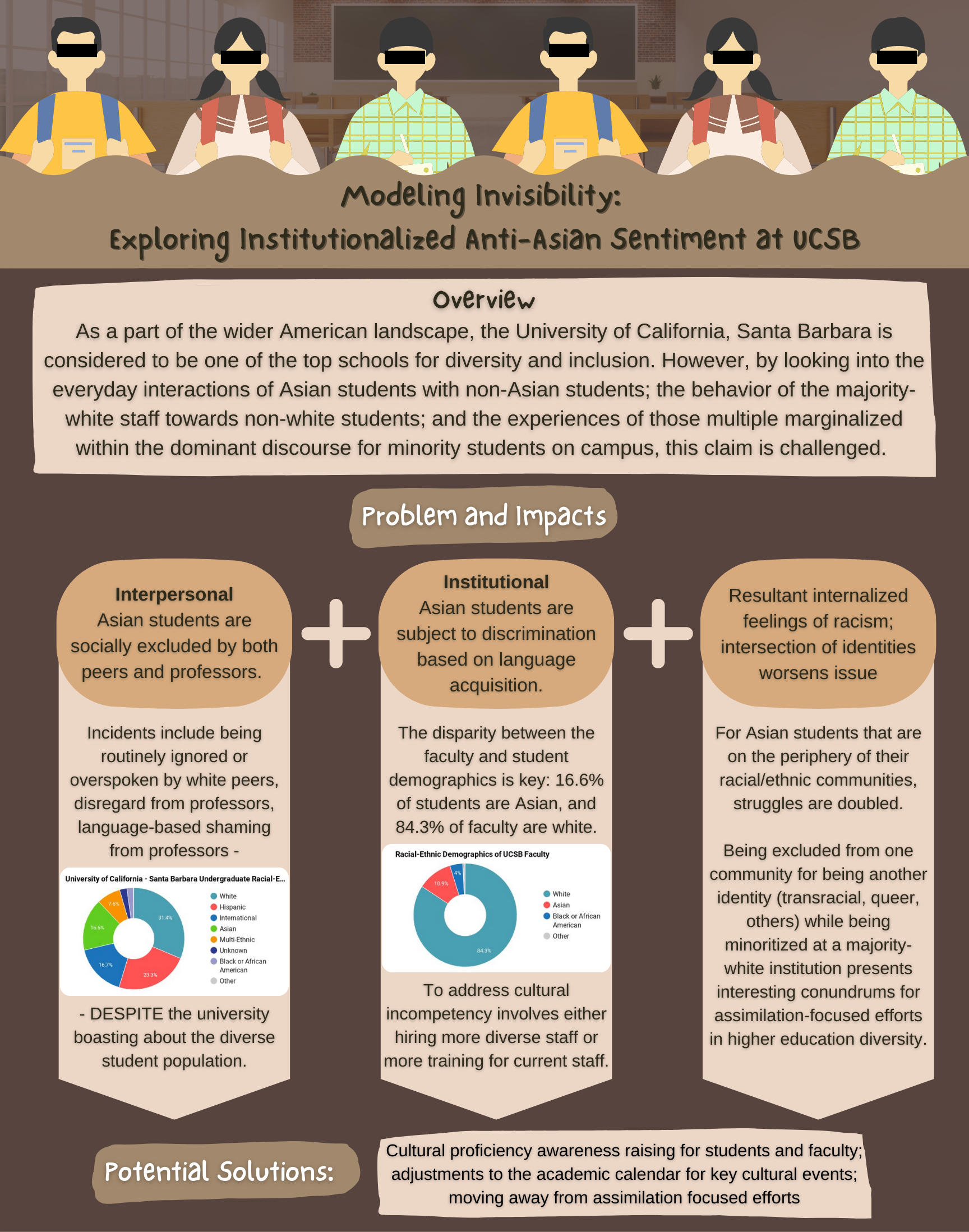

In 2000, respondents to the United States census were able to report themselves as being of one or more races, a change that reveals the socially constructed nature of racial categories. While this adjustment reflects the efficacy of diversity and inclusion politics on a federal level, more work must be done at smaller scale institutions. One unaddressed axis of inequality that is present at the University of California, Santa Barbara is the lack of structural support for Asian students, leading to instances of interpersonal and internal racism. Nationally, this university is in the top 10% of racially and ethnically diverse schools, boasting a larger than average amount of non-white students. Asian students make up 16.6% of the undergraduate population (College Factual 2022). However, these statistics belie the lived experience of minority students on campus. Being ignored by classmates, disrespected by professors, and subjected to cultural disconnect are a few examples of anti-Asian sentiment in practice. In this paper, I will be unpacking anecdotal evidence of discriminatory actions against Asian college students by using critical research on friendships that cross social categories; research on discrimination of perceived assimilation status; and research on the effects of being doubly marginalized through race and sexuality. Drawing from this larger body of work, I problematize the structural practices of UCSB, arguing that the institution itself engenders an erasure of lived difference in favor of a diversity model based on alienating individualism and assimilation.

Being Asian on a predominantly white campus can lead to moments of interpersonal racism, in the form of complicated microaggressions that are not present within intra-Asian social groups on campus. For instance, my East Asian roommate relayed to me an experience she had in a philosophy class she took with our white housemate. She noticed that when the two of them would have small-group class discussions, their white classmates would unerringly make eye contact and talk to our housemate first. Even when she would attempt to speak up before our housemate, she would be sidelined in the all-white class. This happened without awareness from others present. I had a similar situation while meeting with a professor for lunch. The other students present were white and beyond cursory greetings, gave me little regard in their conversation. To understand why these situations are discriminatory, I draw on Suzanna M. Rose and Michelle M. Hospital’s work on the importance of trust for interracial friendships. Research suggests that microaggressions, defined as “commonplace verbal or behavioral indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults” (as defined by Sue et al. 2007), can result in a lack of trust in majority groups by minority groups (Rose & Hospital 2016:78). Unintentionally, majority-group persons in these two anecdotes created an uncomfortable environment for minoritized people to speak up, which can result in self-doubt, feelings of isolation, and other long-term negative effects (2016: 78). On the other hand, juxtaposing these settings with the experience of students within cultural organizations and clubs on campus reveals that this is a legitimate problem by denaturalizing the everyday nature of microaggressions. The label of “Asian” describes people from a highly diverse region (2016: 77), yet the sense of community fostered by resources like the UCSB Asian Resource Center, clubs like QTAPI (Queer & Trans Asian and Pacific Islanders), and other student-led initatives reveal that it is possible to coexist across ethnic/cultural lines while still sharing community. The existence of these campus groups also highlights how the campus’ solution has been insufficient. A change that needs to take place is this focus on student-led groups - there is no cohesive campus program in place that moves towards cultural proficiency, instead placing the onus onto minoritized students to carve a place for themselves in hostile territory.

Student to student microaggressions may not seem like an institutional problem at first, but this is complicated by the relation of professors to their students. For instance, my experience of exclusion from white students involved exclusion from the professor as well. The professor conversed easily with the other students and only after everyone else had left did he turn to me and engage in conversation. My roommate and I are both Asian-American - the problem of invisibility also becomes one of active prejudice when other identity factors are considered, like status as an international student. I have witnessed white professors change in tone and attitude when responding to questions from Asian students that spoke English less proficiently. Accents would noticeably throw these professors off and I have seen instances where the question is not actually answered despite the student being asked to repeat their question, to the growing irritation of the professor. This is a critical oversight of the university - professors are in special positions of power to point out racial indignities, but this cannot happen if they are unaware of the issue at hand or actively contributing to the silencing of Asian students. Drawing again from Rose and Hospital’s work, the support of relevant authorities are proven to reduce prejudice between groups that are in contact with each other (2016:79-80). While the university has focused on cultivating a diverse student body, it has not focused nearly as hard on the faculty hired - 84.3% of UCSB faculty are white (College Factual 2022). The presence of a majority-white staff and increased discrimination based on perceived English language acquisition support the idea that assimilation is the main agenda pushed by the university for their non-white students. It is key that prejudice from professors is based on perceived language acquisition when factoring in results from Michael Gaddis and Raj Ghoshal’s research on roommate discrimination. Discrimination against Indian and Chinese room-seekers changes depending on the immigrant generational status, where those with status closer to whiteness (in using an English first name) were much more likely to succeed in finding a room (2020:9). With all these considerations factored, it is obvious that expectations of whiteness are embedded within the very institution of UCSB, given that the majority-white faculty at times provide education and support of less quality to non-white students. Special considerations must be given to those who cannot speak English at a native level; more focus must be placed on either diversifying faculty or in faculty cultural proficiency.

Having explicated the ways in which interpersonal and institutional racism are present against Asian students at UCSB, I turn now to the interplay of institutionalized racism with theinternal and the intersectional. The sidelining of Asians may seem initially innocuous, but the cumulative effects of smaller-scale microaggressions are part of structural issues at UCSB. An article published by UCSB’s Daily Nexus newspaper provides perspective on other students’ experiences, specifically regarding how Lunar New Year celebrations look much different at a college campus. Of note is Toni Shindler-Ruberg’s concise statement, “I turned down the Lunar New Year dinner. I had to study for midterms” (2022). In the United States, people are only given days off for federally recognized holidays. For people from other cultures, this means thatmany important cultural holidays are not considered. It becomes a matter of choosing between community and academia. The university boasts a commitment to diversity and opportunity for all - one way to demonstrate this would be to organize academic calendars inclusive of major holidays like Lunar New Year so that non-white students do not have to choose between community and their grades. Another point present in this article is the sense of double disconnect experienced by students who do not fit into the image of the ‘ideal’ minority figure. Yiu-On Li and Alice Zhang both mention being raised in America and Shindler-Ruberg discusses the experience of being a transracial adoptee (2022). This double bind is not an uncommon experience. Extending the discussion past the specific event of Lunar New Year, this article highlights how there are Asians at the margins of visible Asian experience. Chong-suk Han’s work with understanding gay men of color’s exclusion from white-centric queer spaces serves as a tool in understanding this struggle. His work finds that racism in gay communities is actively maintained through excluding non-white subjects; however, homophobia in racial/ethnic communities is actively maintained, resulting in increased marginalization (2007:54). The invisibility of queer Asian students, which seems to be shared by transracial students, make for a potential site of future research on the negative affects of ‘over-assimilation,’ which seems to lead to increased feelings of internalized racism and self-hatred due to alienation from an ethnic community.

As a part of the wider American landscape, the University of California, Santa Barbara is considered to be one of the top schools for diversity and inclusion. However, by looking into the everyday interactions of Asian students with non-Asian students; the behavior of the majority-white staff towards non-white students; and the experiences of those multiple marginalized within the dominant discourse for minority students on campus, this claim is challenged. While the university has implemented solutions like student-run organizations and clubs, more must be done to address the active exclusion of Asian students on campus. Some suggestions for this problem include cultural proficiency awareness raising for students and faculty and adjustments to the academic calendar for key cultural events. Moving away from assimilation focused efforts by the institution would be critical in supporting Asian students.

References

College Factual 2022. “UCSB Demographics & Diversity Report.” Media Factual. Retrieved June 9, 2022 (Source Link).

Gaddis, S. Michael and Raj Ghoshal. 2020. “Searching for a Roommate: A Correspondence Audit Examining Racial/Ethnic and Immigrant Discrimination among Millennials.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6:1-16, DOI: 10.1177/2378023120972287.

Han, Chong-suk. 2007. “They Don’t Want To Cruise Your Type: Gay Men of Color and the Racial Politics of Exclusion.” Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation, and Culture 13(1):51-67, DOI: 10.1080/13504630601163379.

Li, Yiu-On, Toni Shindler-Ruberg, and Alice Zhang. 2022. “A Late Look at Lunar New Year 2022.” Daily Nexus, February 8. Retrieved June 9, 2022 (Source Link)

Rose, Suzanna M. and Michelle M. Hospital. 2016. “Friendships Across Race, Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation.” In The Psychology of Friendship. Oxford Scholarship Online. Retrieved June 9, 2022 (SOURCE LINK UNAVAILABLE)